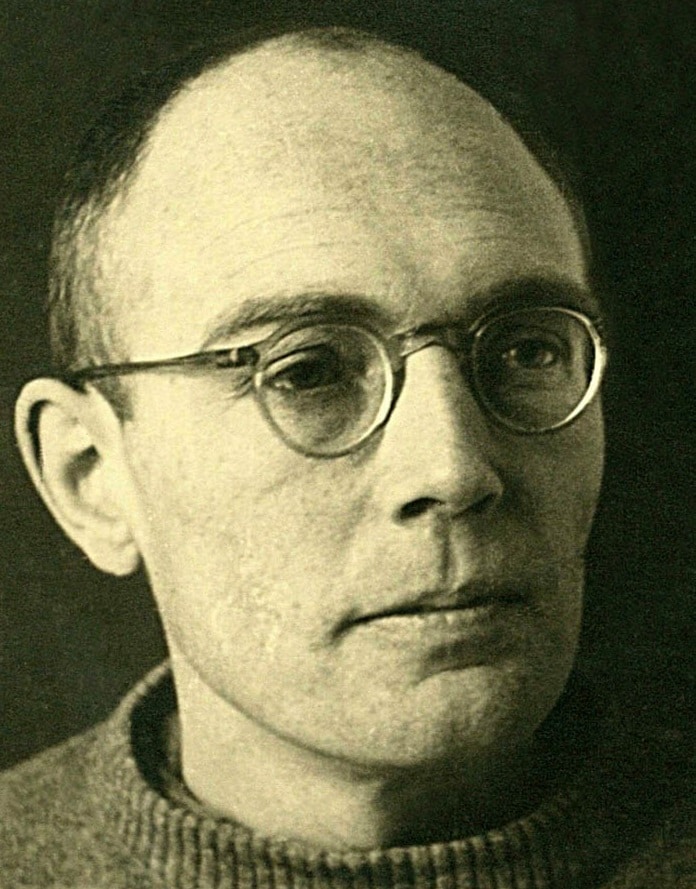

June 23 marks the 25th anniversary of the beatification of Karl Leisner by Pope John Paul II in Berlin, while he was visiting Germany. Who was this man, the only deacon who was ordained as priest in a concentration camp during the Second World War, under the strictest secret, and whose strength lied in his Covenant of Love with the Blessed Virgin and his passion for Christ?

Christ – my passion

Every life can be determined by who we encounter, where and when. This is also the case with Karl Leisner. Born on February 29, 1915, he became a member of the Catholic Youth Movement when he was a student in high school. There, in 1925, he met a priest who caused a deep impression on him: Walter Vinnenberg, religion and sports teacher. The teacher’s ideals and the ideas of the youth movement gave Karl experiences of community with young people, exposure to great travels and the enthusiasm for music and singing. He formed an intimate relationship with the Holy Scriptures, the Mass and the Eucharist. He did everything possible so that the youth he led would become Christ’s youth and would not fall for the Third Reich’s ideology. In his diary he wrote: “Christ – You are my passion!”. Convinced that he wanted to become a priest after graduating from the institute in 1934, he started studying theology in Münster.

Münster’s bishop, Clemens August, quickly realizing Karl’s extraordinary qualities working with the youth, entrusted the 19-year-old young man as youth diocesan leader. This entailed being responsible for more than 30,000 youngsters between the ages of 10 and 14, in whom Karl wanted to ignite a passion for Jesus filled with joy, motivation and energy.

During the semester when he left school in Freiburg and while working on his next mandatory labor service in the summer of 1936/1937, he met Elizabeth, his landlady’s daughter. During this time, he felt strong internal battles: priesthood or marriage and family? On Easter 1938 he wrote on his diary: “Lord, I thank you for sending this beautiful and faithful young woman into my life.” Finally, after difficult struggles, he decided to become a priest and wrote a farewell letter to Elizabeth in which he said: “I thank you for your kindness and your sisterly love. I owe you much, and Christ has found me in you as he had never found me before.”

Karl was ordained as a deacon on March 25, 1939, hoping to be ordained as priest a few months later. But he was suddenly diagnosed with severe tuberculosis, which forced him to enter a pulmonary sanatorium for treatment.

While in the hospital, he uttered a phrase that would cost him dearly: “A pity that I wasn’t there”, referring to the attempt on Adolf Hitler’s life by Georg Elser on November 8, 1939. This led to his detention when his roommate reported him. After several stays in various prisons, he was sent to the priest’s quarters in a concentration camp in Dachau where more than 2,700 priests from 23 different countries lived, including Schoenstatt’s founder, Father Joseph Kentenich.

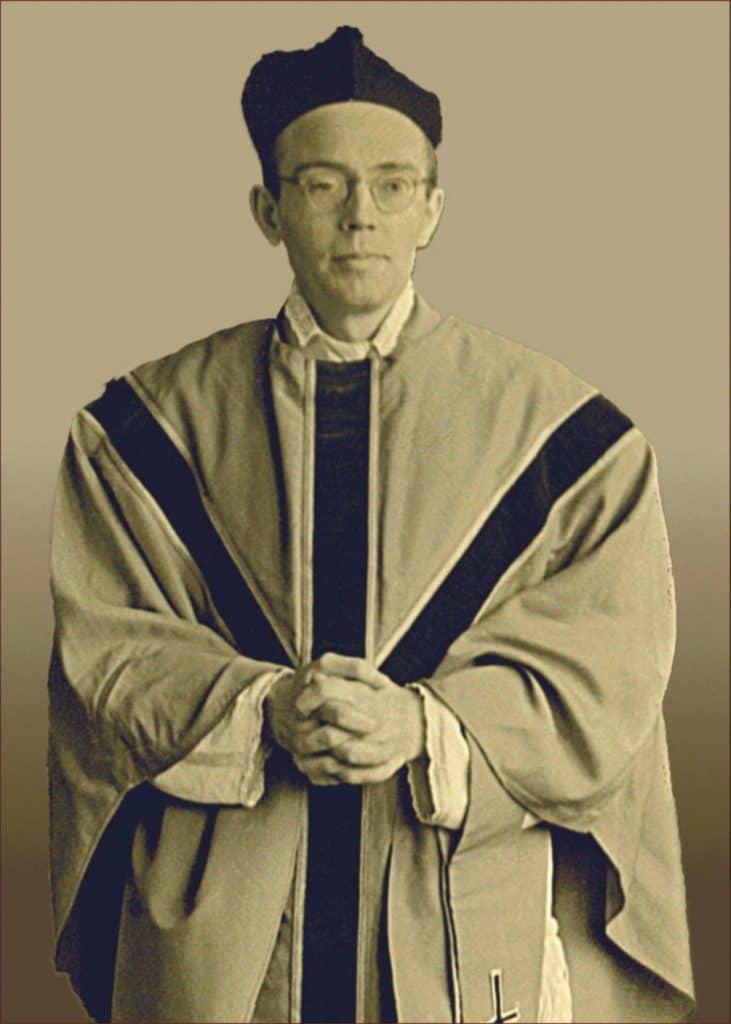

His lung disease resurfaced with potency. Knowing that he did not have long to live, the Holy Scriptures and the Eucharist, kept secret, became a great comfort to the young deacon. In keeping with his ideal of serving others as a priest, he accompanied his fellow prisoners spiritually and materially despite his illness, smuggling consecrated hosts to the sick and countless dying. Many recounted how he encouraged and delighted the prisoners with prayer, meditations and musical entertainment. Until 1942, he met with a secret Schoenstatt group founded in the camp called “Victo in vinculis” – victors in chains – which also included Father Kentenich and Father Joseph Fischer. He had a strong desire to be ordained as a priest, which seemed impossible, since there was no bishop among the prisoners. But the unexpected happened: in September 1944 a French Bishop, Gabriel Piguet de Clermont, arrived at the Dachau concentration camp.

Karl’s wish was presented to the bishop, and he agreed to ordain him. Preparations for the celebration were made quickly and secretly: a letter was sent from the camp to Karl’s home bishop asking for permission to ordain him, episcopal vestments and insignias were secretly made from the simplest materials, candlesticks were made from tin cans. On Gaudete Sunday, December 17, 1944, Bishop Piguet secretly ordained the seriously ill deacon in Block 26, risking the lives of all involved. Numerous imprisoned priests from all over the world laid their hands on him. He himself was only able to participate in this celebration with the utmost effort. Days later, on St. Stephen’s Day, he was able to celebrate the first and only Holy Mass of his life.

He was freed from the concentration camp on May 4, 1945. He spent his last weeks in the lung sanatorium in Planegg, near Munich. Two thoughts still remained with him: love and atonement. He died on August 12, 1945. His last diary entry, on July 25, 1945, read: “Bless also, Most High, my enemies!”

Related posts

April 24, 2024

We have a Shrine because there are pilgrims

It took me about twenty years before I could understand the significance of an experience I had as a child and realize how consistent it…

April 18, 2024

Covenant of Love Day: Becoming Prophetic, Like Mary

Dear Schoenstatt Family all over the world, Greetings on the celebration of the Covenant of Love Day. We remember with gratitude and joy…

March 19, 2024

Saint Joseph: Radical service leadership

When we talk about leadership, we tend to bring to mind the image of people of great public or private reputation, with decision-making…